WOODTURNING WITH RESIN

Even industry-standard dry wood is considered too wet for casting (remember that any contact with water creates unsightly foaming, bubbling, and hazing in urethane resin), but it is closer.

If you try to dry out burls with high moisture content, the moisture will leave the wood rapidly, causing internal checking in the wood. The next step is to dry the wood out further by baking it.

Since different woods lose moisture at different rates, it is impossible to tell how long this process will take.

The Three Golden Rules: An Overview

Over the years and hundreds of casts, I have developed a set of rules that must be followed to have successful casts. I call these categories the three golden rules of casting:

Preparation, Product, and Pressure.

PREPARATION: The Wood

Proper preparation of any wood in your project is the first and most important part of casting with urethane resin. You’ll need to clean the wood and make sure it is dry.

In some cases, the wood will need to be stabilized; not there are plenty of types of wood that can skip this step.

Clean the Wood

Select a piece of wood that has been stored in your shop for about a year. The first step in preparation is to make sure the wood is clean.

It must be clear from dirt and grime, and all bark should be removed from the wood. This is important. You do not wish anything to get between the resin and the wood.

This step will ensure a good bond. You will need these tools: a wire brush, dental picks, and a chisel.

Remove Moisture

Once the wood is immaculate and free of bark, it’s now time for the most critical step in casting, urethane-making sure to remove all moisture from your process.

Moisture and urethane resins do not get along and will cause a reaction, whether you’re casting with wood, plastics, or just resin.

When you purchase a piece of wood, there will always be moisture in it. There are two terms to describe who the wood is: dry” and green.

Greenwood has a high moisture content, usually 20% and above. Even industry-standard dry wood is considered too wet for casting (remember that any contact with water creates unsightly foaming, bubbling, and hazing in urethane resin), but it is closer.

Most burls on the marker are freshly cut, with very high moisture content, such as 30-40% moisture. These burls will need to sit until the moisture level is about 17%. When I buy burls, I plan to use them next year.

If you cannot wait that long, try to find a seller with burls that are not freshly cut. If you try to dry out burls with high moisture content, the moisture will leave the wood rapidly, causing internal checking in the wood.

It will be hard to see the cracks until you begin to turn the wood, but this is a look you will not want in your finished piece.

The next step is to dry the wood out further by baking it. Since different woods lose moisture at different rates, it is impossible to tell precisely how long this process will take.

It will take hours, and for some larger pieces, it could take days. Standard moisture meters do not read below 5 %.

When your meter does not respond in multiple spots and is cool enough to touch safely with your bare hands, the wood is now ready to be cast right away if it doesn’t need to be stabilized.

We spent all this time and energy removing moisture from the wood; if you are not going to cast or stabilize right away, it is essential to wrap the wood in plastic wrap (vacuum-sealed bags are even better) until you are ready to go to the next step.

Humidity in the air will absorb back into the wood; in a short time, the piece will be back up to 6-9% moisture opening your project up to a failure.

STABILIZING: If Needed

This step is not always needed. It is technically part of the Preparation rule, but I’ve broken it out here for clarity because it can sometimes be skipped.

What is stabilizing? This is the process of using a vacuum chamber and vacuum pump to create the right conditions to thoroughly saturate a soft piece of wood with stabilizing resin (note this is a different product than urethane resin).

This resin is activated with an external heat source (an oven), which stiffens the wood fibers, making them extremely rigid and stiff.

This process allows you to take a spalted, or punky, piece of wood and make it as hard and dense as an exotic species like ebony or a piece of Australian burl.

You will need to stabilize any wood, including the buckeye burl, maple burl, spalted woods, and pine cones.

Not Always Needed. Before we go too much into this phase of working with resin, I want to state clearly that plenty of projects you can create do not require the additional step of stabilizing wood.

You create your blank either entirely out of resin or use a wood that does not need to be stabilized. There are plenty of woods to choose from walnut, mesquite, cocobolo, Australian burls, and any tough and dense wood.

You could create turned resin and fusion resin pieces for years and never need to bother with stabilizing. I didn’t start stabilizing woods until after working with resin for three years.

However, once you are comfortable with resin turning and want to take it to the next level, you can broaden your choices even more by working with stabilized woods.

You’ll need three new items: a vacuum chamber, a vacuum pump, and stabilizing resin.

Why Stabilize?

There are four main reasons for turners to stabilize. Punky woods have a unique look but will tear out while turning if unstabilized.

We all know about seasonal wood movement, but by filling the spaces in the wood with hardened resin that humidity would generally get into, the wood is no longer affected by humidity and will not move.

Stabilizing also seals the wood so any dye cannot stain it in the resin. For example, if you combine red-dyed resin with a light-blonde piece of maple burl, you will end up with pinkish maple in place- mainly the grain.

(If you’d instead not get into stabilizing yet, you can work around this problem by using only darker woods or mica powders instead of dyes with light hardwoods.)

The final reason is balance. Resin weighs more than unstabilized wood; turning blank with an unbalanced, uncentered weight can be challenging. Adding stabilizing resin to the wood balances the blank.

Necessary Tools For Woodturning With Resin

Even industry-standard dry wood is considered too wet for casting (remember that any contact with water creates unsightly foaming

Several vacuum chambers are on the market, including the Glass Vac and TurnTex JuiceProof. Get a two-stage rotary vane vacuum pump; it can reach a deep vacuum.

The goal is to remove all the air from the chamber and the wood. Unlike the air compressor, when pressurizing, the vacuum pump must remain on the entire time; don’t worry about burning up your pump because running for long periods is what these pumps are designed to do.

Stabilizing at a Glance

Here’s a quick rundown of the stabilizing process. Place the wood in a vacuum chamber and completely submerge it in a stabilizing resin.

A vacuum pump then removes the air from the chamber and, more importantly, the wood, allowing the resin to permeate.

When the bubbling stops, all the air has been sucked out of the wood and out of the chamber.

Open the valve and shut off the vacuum pump, allowing air back into the chamber. (Note: If you turn off the pump without opening the value first, the vacuum inside the chamber can pull oil out of the pump and contaminate the resin.)

When the air is reintroduced into the vacuum chamber, it pushes down on the resin; the resin will absorb right away. You will notice the resin level drop very quickly when the valve first opens.

To ensure deep penetration, the wood must soak in the resin.

Many people think that the resin is being pulled into the wood while under vacuum, but this is not true. Think about submerging a dry sponge underwater; very little water will absorb into the sponge because of all the air that is in its way.

When you crush the sponge in your hand underwater (like creating a vacuum), the air is released. When you open your hand underwater (like releasing the vacuum), the sponge can absorb all the liquid it can hold.

Now it is time to let the wood soak in the resin. It is difficult to say how long this process will take. I have left large pieces of buckeye in for days to make sure resin gets fully absorbed deep into the wood.

Just remember, it’s not possible to oversoak the wood.

The stabilizing resin then needs heat to set and become rigid, so the wood goes back into the oven. After any bleed-out is removed from the surface, the wood is ready for casting or storage.

Once a piece is stabilized, there is no way for humidity to enter the wood. For six months, I’ve had pieces on the shelf that went into a casting with no issues.

One trick is to place the block in the oven for a few minutes before casting to ensure no surface moisture on the wood.

PRODUCT: The Resin

Product-urethane resin itself is the second golden rule of working with resin. After figuring out how much resin you need to fill your mold, the next step is to measure and mix the resin correctly. There are a few common mistakes at this stage.

Measure the Correct Amount. Many resins, including the product used throughout this article called Alumilite Clear Slow, have a 1:1 mix ratio by weight.

This means you need equal weights of Part A and Part B resin components. If you do not have the correct measurements, your pieces can turn a hazy white color instead of clear, or there can be soft areas.

The easiest way to measure out the resin is to place a clear container on a scale, tare the scale, pour in Part A until you reach half the needed amount, and next top off with an equal volume of Part B.

Note: It doesn’t matter which part you add to the other. Any scale will do, but I prefer a digital scale with a gram weight feature. The tolerances are very tight when you measure by grams, ensuring an accurate blend.

If you are off a few grams due to a long pour or the scale not catching up in time, you can add a proportional amount of the other part, so the extra part is not wasted.

However, with the size of the projects, we are working on in this book, being a few grams off does not affect the end product.

If you have a brand of resin that measures by volume, you will need a mixing cup with volume measurements. The process is basically the same as my weight, but you don’t need a scale. Pour each part into the correct line on the cup.

Mix Thoroughly. If you get lazy with the mixing process, your blanks will not cure properly. I prefer to mix my resin with a drill attachment in clear containers so I can see that it is properly mixed.

Don’t add color until you can see the base is combined. Use a scraper to make sure any material stuck to the sides and bottom gets mixed in-they will not unless you take special care. Don’t worry about mixing bubbles into resin because the pressure pot will take care of them.

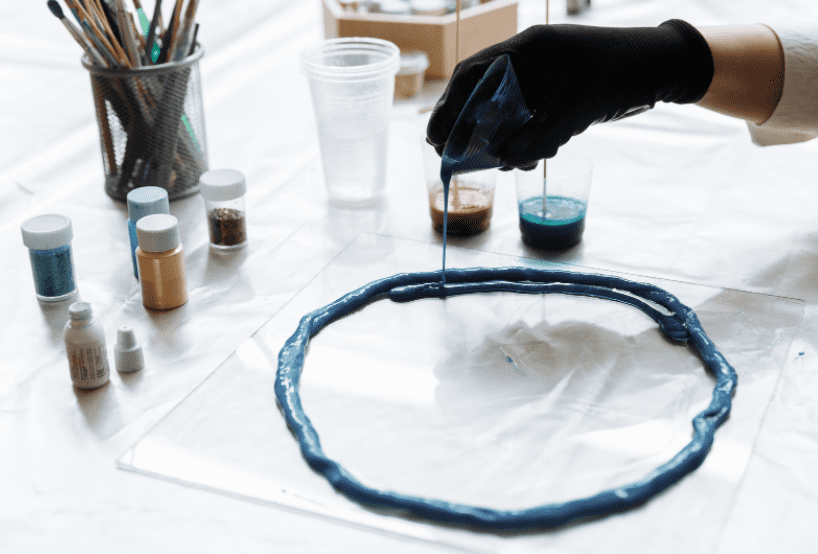

Add Color

A great part of working with the resin is the ability to add dyes to make your own custom blanks. It is essential to know whether the pigments are compatible with the resin.

For example, urethane resins react violently with moisture, so do not use a water-based pigment. I find it best to use dyes sold by the manufacturer of the resin I use, as I know they will be compatible, and there will not be any failures in the end product.

Another option is mica powders, which reflect the light to give your blanks a whole new dimension. Because mica is made of individual small solid colored flakes, you can add batches of resin with different-colored mica powders to a mold to make a swirl of distinct colors.

This is difficult with dyes, as they will mix into a brown color.

I recommend naming the color blends you come up with and keeping a recipe book of how much resin you mixed with what dyes so you can repeat the results.

Timing and Temperature

There are a few important times to remember when working with urethane resin. Open time (also called work time and pot life) is when the mixed resin will remain in liquid form, a.k.a, how long it remains workable.

This is how long you have from the second you combine the parts to get the resin under pressure so that the bubbles are removed before the piece cures.

To provide more detail: When you mix Parts A and B, you kick off the chemical reaction that ends in a cured blank. The chemical reaction is exothermic, meaning it creates heat as it cures.

Open time is how long you have until the heat starts curing the piece; to be precise, manufacturers usually provide an exact temperature and sample mass with their open times.

Alumilite Clear Slow had a 12-minute open time (100g at 75° F), so I am to get the mold in the pot in 10 minutes so the pot can pressurize in time.

If you can feel the warmth coming off your resin, the reaction has begun in earnest, and the resin is starting to harden.

I do not recommend pouring resin into the mold after that because the pressure pot will not be able to pulverize all of the bubbles; your project will not have the nice, clear quality you want.

You also do not want the ambient temperature or the temperature of the resin parts to be too high while working the resin, as that will shorten the open time even further.

Most open times are calculated with ambient temperatures of 75° F. As you can imagine, the more resin you mix, the more heat is created. This means that larger batches have an even shorter open time. You can combat this by chilling the parts before mixing.

Demold time is how long it takes until the mixed resin is hardened enough to remove from the mold. Alumilite Clear Slow has a demold time of 4 hours, so I like to leave my pieces in the pressure pot for no less than 4 hours, but I’ve left pieces in the pot for as long as two days.

For the most part, 4 to 6 hours is sufficient. I often cast right before the end of the day and let it sit in the pot overIt’s night. This ensures a proper amount of time in the pressure pot.

Cure time is the amount of time until the casting has completely hardened. Clear Slow has a cure time of 5 to 7 days.

The time period between demold and cure time is when you want to turn the piece. I usually recommend waiting until 1 or 2 days after demold time has passed. Make sure that you read and understand the timing instructions of the particular resin that you are using.

PRESSURE: The Pot

Pressure is the third golden rule. Due to the limited open time of urethane resin, a pressure vessel must be employed to make clear blanks.

In partnership with an air compressor, a pressure pot employs air to move on the blank, squeezing the air bubbles so they are too small to be detected by the human eye-then, the resin heals under pressure so that the bubbles are never obvious.

You can purchase a pressure pot (such as the 5-gallon model made by California Air Tools) or convert a painter’s pot. Even though most paint sprayers operate at about 20 psi, the tanks are certified for much more.

Especially if you want to cast larger pieces, you may have to convert a larger paint pot yourself. It is best to purchase a ready-made pressure pot unless you are experienced with the conversion process.

Get a compressor with a tank similar to or larger than the pressure pot. The air compressor tank can be smaller, but you will find that it will take longer to achieve the required psi due to the constant cycling to fill the pressure pot.

It would help if you also did a dry run first with an empty pressure pot to see how long it takes to achieve the desired psi in the pressure pot. The last thing you want is to have your casting fail because your pressure pot takes too long to get up to pressure.

Optimize Pressure

How to get resin out of the wood mold. Before I answer the question about how much pressure to use, let me explain best practices for optimizing pressure through correct mold construction.

You want the air pressure to make tact with the resin and do what it needs to do. It is important never to stack anything on top of your mold or restrict that contact.

This is likewise why I select to employ horizontal molds-they give the air pressure more surface area to push down on the resin. A larger surface will allow you to use less pressure.

For example: If you are casting a handle blank and you have a horizontal mold that is 6″ x 11/2″ x 11/2″, that gives you nine in of exposed surface that only needs to be pushed down 11/2″ to pulverize the bubbles.

Doing the same blank as a vertical pour will be a little more difficult as you only have 21/4 in2 exposed, and the air pressure will need to compress 6″ of resin.

There is a greater chance of air bubbles in the vertical pour than in the horizontal pour.

How Much Pressure?

On smaller pours, 40 to 60 psi can be used, but on larger pores (anything over 2″ thick), 80 psi is required to ensure enough pressure to pulverize all the bubbles.

80 psi is the sweet spot that will work for any project; however, not all pressure pots can handle that level of pressure, and it is essential NEVER to exceed the working pressures of your pressure pot.

All pressure pots are not created equal and have different ratings

You can skip the Preparation rule-it; it focuses on prepping wood and start with blanks made of 100% resin.

If you are new to resin, you can get a feel for the process more quickly. Next, revisit the Preparation info to incorporate some wood that doesn’t need to be stabilized.

When you feel confident with that, add stabilizing wood to your repertoire.

WHEN TO SKIP AHEAD

WHAT NEEDS TO BE STABILIZED?

Stabilize:

- All softwoods

- Pinecones

- Most burls, including buckeye, maple, and spalted woods

Don’t Stabilize:

- Walnut

- Mesquite

- Cocobolo

- Australian burls

- Any tough and dense wood

important to know that a 1:1 ratio measures, not all resins. Some are measured by volume, others by weight.

A WORD ABOUT PRESSURE POTS

If you have a painter’s spray pot, it can be converted to a resin pressure pot. There are plenty of videos available online if you are interested in the process.

However, make sure you fully understand and are comfortable with the conversion process. If you are uncertain, you should definitely purchase a ready-made pressure pot.

There are several companies to choose from. Read all the instructions and any other material you can find until you understand the ins and outs of working with pressure pots.

Don’t be intimated; plenty of people work safely with them every day. Your pressure pot is key to making beautifully clear resin blanks.

You need to follow your pot’s guidelines and never exceed the pot’s pressure rating.

Article based on the Book:

Techniques and projects for turning works of art

Author: Keith Lackner